In 2004, Galesburg’s Maytag Manufacturing plant closed. The factory workers who made the last refrigerators bought three, signed them, and wrote “ THE LAST TOP MOUNT REFRIGERATORS PRODUCED IN GALESBURG, ILLINOIS WITH ‘PRIDE’ BY MEMBERS OF IAM LOCAL 2063 SEPT 14TH , 2004.”

Observing this as a child, Moreno watched a site become defined by a narrative of industrial manufacturing’s exodus. A narrative of absence set in, charged with the discomfort of inhabiting a vacuum’s negative space. “Galesburg, a good place to die” rode on cars’ bumpers. He asked “what does it mean to grow up in the end? What happens after the end?”

The works in Alloy began with formally asking these questions in 2014 and continue to be generative.

To cut, to grind, to cast, to repair, to strip, to cover, to transfer, to transport, to arrange, to bandage… building things underscores an ambiguity around material endings and beginnings. A woodworker’s labor begins with a tree’s ending: to extend the life of a body with its own graining, subtle coloring, an aura, that will exist this once—never to reappear. The tree’s body is a substance with unique fault lines that informs what the woodworker will do. It is saturated with inheritances.

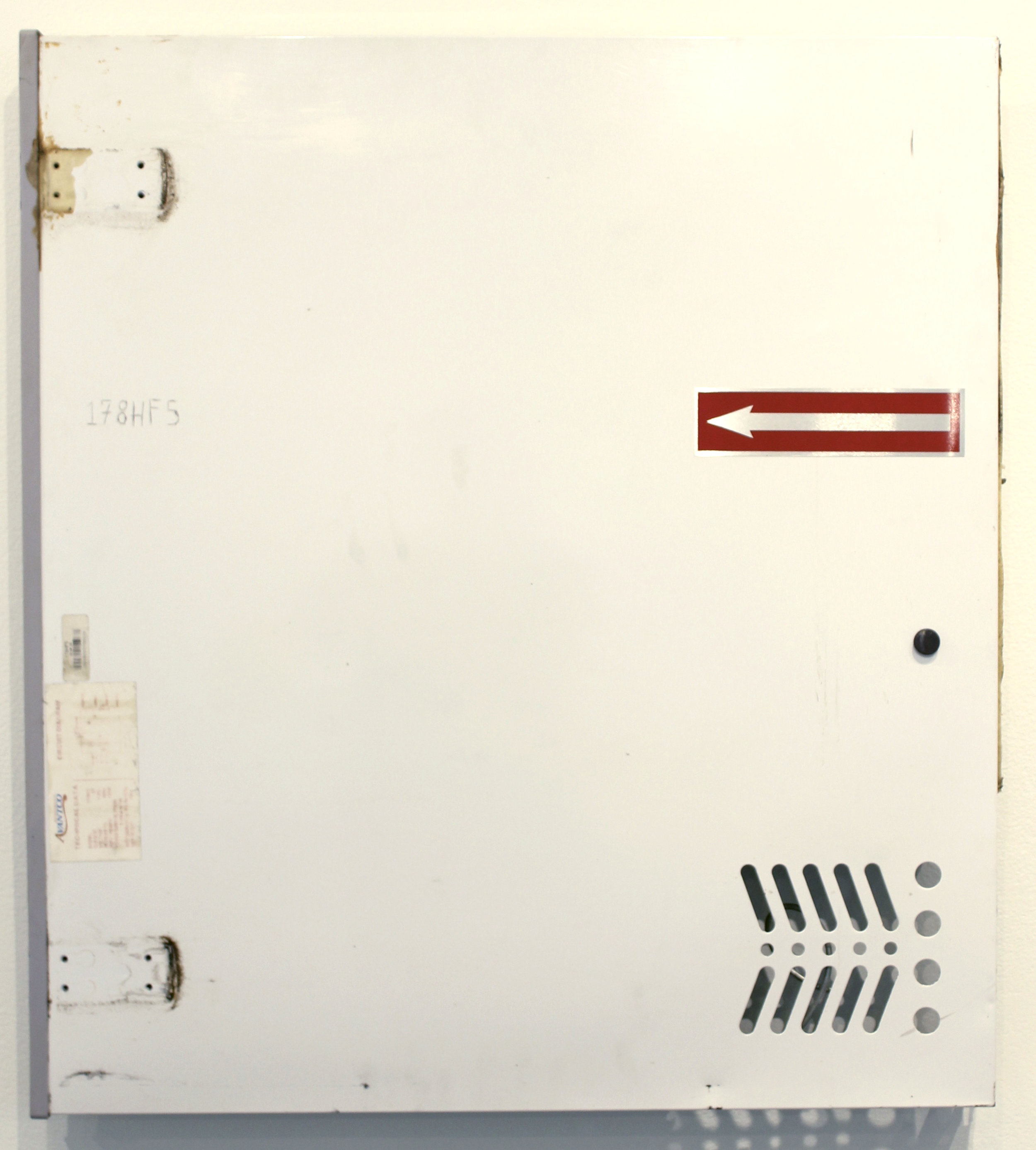

Responding to refrigerators accordingly, Moreno approaches them as a site to linger with the emergence of industrial nostalgia as a persistent animating sentiment within American social life. Can the capacities of craftsmanship—a repertoire of skills and ethics — both acknowledge such loss and critique the desires for return? What do these objects have to say as sculpture that persists, fails, and cultivates a beauty from having lived? As a fallen tree is stewarded into new form, the symbolic fault lines of refrigerators are rendered legible so they might be alloyed anew.